Back When America Was "Great"

Revisiting Chester Himes' forgotten classic If He Hollers Let Him Go.

Although I started this Substack to ostensibly avoid politics, some encroachment into the realm of the political is inevitable as the USA shuffles towards fascism at breakneck speed. Lately, in attempting to avoid the news, I, instead, end up absorbing it through osmosis, which is unavoidable; the awfulness is unfortunately gleaned while perusing headlines unwittingly with peripheral vision. Or I get into a “discussion” with some MAGA idiot and end up getting called “woke” without having even mentioned anything remotely concerning social justice.1 Reminder to anyone who has to deal with this “logic:” When a MAGA blowhard uses the acronym DEI, what he or she really means is, “I don’t like N’s.” Just substitute the verboten N word for DEI and their worldview makes perfect sense. Hence, I feel like revisiting one of my favorite books by a black writer, one who was indeed writing when America was supposedly “Great,” during World War II. The book, If He Hollers Let Him Go is an all but forgotten classic that paints a brutal portrait of life on the San Pedro waterfront during Jim Crow.

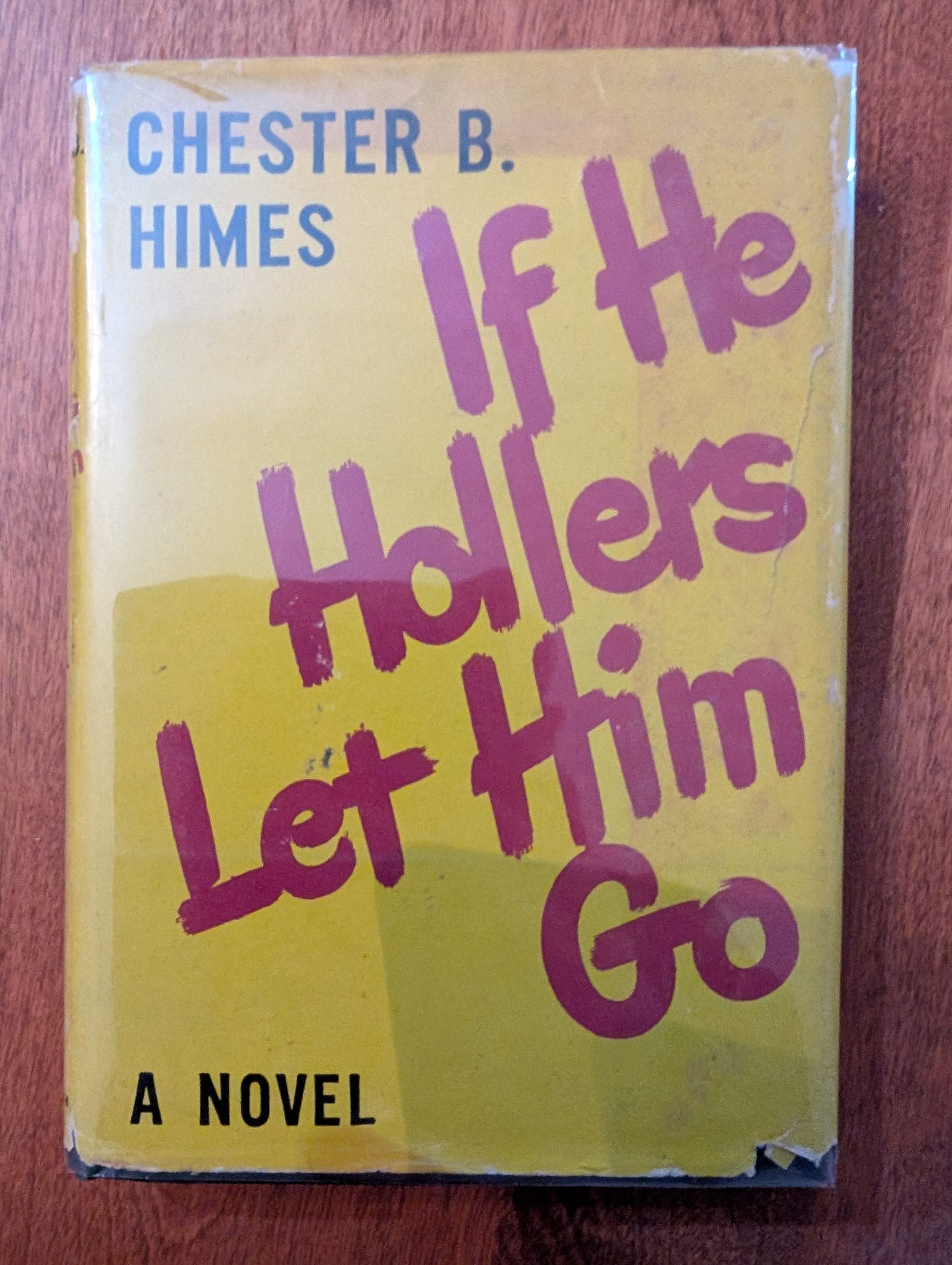

Photo: My first edition, for which I overpaid, of this forgotten classic first novel.

If He Hollers Let Him Go by Chester B. Himes. Doubleday Doran, 1945.

If He Hollers Let Him Go is a no holds barred brutal account of the life of a black man working in a Los Angeles (San Pedro) shipyard during the pre-integrated Jim Crow society that was America during WWII; since black labor is needed during the war, some integration is tolerated, albeit reluctantly, which leads to even more overt racial hostility. Forget the microaggressions that make for so much useless news fodder nowadays, Chester Himes depicts a world of outright hostility by whites, a.k.a. “peckerwoods,” whose liberal use of the ‘n’ word appears on virtually every page, enraging the protagonist, Robert Jones.

Jones sees society through racial lenses, and from what he encounters, it is hard to argue with his pessimistic take on Jim Crow America. Peckerwoods harass him daily. His girlfriend, a lighter skinned black, is privy to social circles that exclude darker hues like his. His job in an ostensible supervisory capacity at the shipyard excludes his ability to ask any white laborer for help with a task, lest he—or in this case she—drops the 'n' word on him. Not to be undone, Jones retorts one day with “Cracker slut,” which brings about completely predictable results. The plot, which takes place over a mere few days, is inevitable. Racism is overt and endemic. The black man is bound to lose. No matter whether it be the Invisible Man, Rufus Scott, or Bigger Thomas the black protagonist can only correctly see his fate vis-à-vis white society; he cannot not alter it.

Chester Himes’ If He Hollers Let Him Go stands as a testament to what one hopes is a bygone era where people are primarily judged and pigeonholed by the darkness of their hues and their gender. Himes presents a pecking order within a society obsessed with race to the point where the narrative could stand as a sociological document, a J’Accuse against peckerwood society. His detailed account of labor in a shipyard has all the verité of Melville’s Pequod.

Amidst this squalid farrago of misogyny and racism is deliberately provocative writing. Any prescient undergraduate instructor in 2025 academia2 would nix teaching this novel in a nanosecond. It’s ability to offend, or at the very least, disgust, knows no bounds. Witness the wish-fulfillment of imagined rape in the passage below:

She was a peroxide blonde with a large-featured, overly made-up face, and she had a large, bright-painted, fleshy mouth, kidney-shaped, thinner in the middle than the ends. [. . .] She looked thirty and well-sexed, rife but not quite rotten. She looked as if she might have worked in a cat house, and if she hadn’t, she must have given a lot of it away. (Pg. 19).

So, what to do with this novel, which should serve as a triptych of required reading narrated by alienated black male protagonists, the other two being Native Son and Invisible Man? The outlook is bleak and—as I mentioned above—inevitable. The only question for a reader is the minuscule difference in nuance between the fate of the Invisible Man and Bigger Thomas and Rob Jones. Of the three novels, If He Hollers Let Him Go seems to be the one that is relegated to all but forgotten status.3 A shame because—although it slogs towards the end—it is less mired in the bootless communist ideology that hijacks Invisible Man. If He Hollers Let Him Go is a brutal kick in the balls for all peckerwood readers.

Incipient fascism trumps racism. And then the two feed off each other. . .

Can an instructor even teach this book in a blooming dictatorship and circle jerk of white anti-intellectuals?

Invisible Man was still pretty much required reading when I was an undergraduate. Wright—admittedly—is not read much anymore. However, Himes is primarily remembered for writing potboiler genre detective novels, and not his stone-cold classic debut novel which is all but forgotten and only in and out of print in obscure paperback imprints with lousy font.

Hey David, your review of this novel has compelled me to put it on hold at the SPL. I also enjoy the descriptions of gritty labor and racial relations in the 1950s USWC. Have you read Pick Up by Charles Willeford? More focused on the street life of 1950s California but also with an interesting take on racial relations.