On the Disdain Women Feel: Nelly Arcan's Phenomenal Debut Novel, Putain, Revisited

Reviews an Essays on Transactional Sex (Part V)

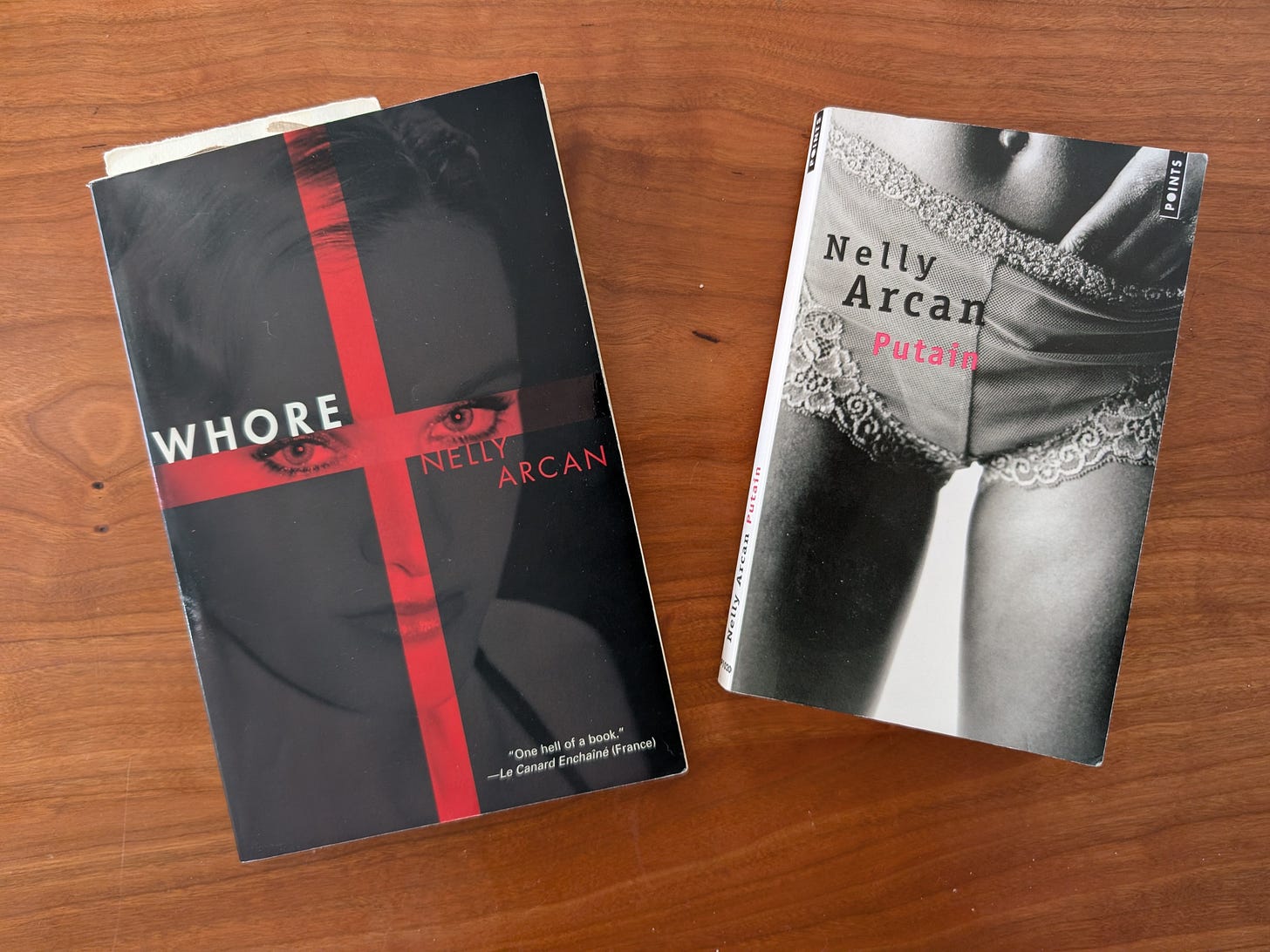

Photo: My dogeared and well-annotated copies of Nelly Arcan’s debut novel. As I write in a footnote below, the novel is anything but salacious, as the French mass market paperback design falsely implies.

Putain by Nelly Arcan, Éditions du Seuil, 2001. English translation, Whore, Black Cat press, 2005.

There has never been a better book for shattering male illusions than Nelly Arcan’s debut novel Putain (2001), in English, Whore (2005). It should be required reading for all heterosexual men and particularly those who ever went through a Henry Miller or Beat stage revering writers who left a literary testament that rationalizes and glorifies the purchasing of women as some sort of sexual liberation. Perhaps transactional sex might lead to some sort of liberation, but—and here is the rub—only for the men. Nelly Arcan makes this crystal clear.

Arcan’s voice is brutally honest, particularly since she worked as an escort in Montreal during her student days and is writing based on actual experience. Although fiction, Putain most likely incorporates many accurate details. It is doubtful, though certainly not out of the question, that an escort of Arcan’s pulchritude and youth worked in a dingy furnished room seeing multiple clients for an hour each day, sweeping their mostly gray hairs under the bed between assignations.1 However, all the mundane details are frightfully relevant because Putain is—first and foremost—an interior monologue to her psychoanalyst that unveils the despair that Arcan’s fictional heroine, Cynthia feels. “Cynthia,” of course, is a pseudonym, much like “Nelly Arcan.”

It would take a literary detective to uncover the discrete untruths of various details, the literary license that Arcan, née Isabelle Fortier, invokes in her writing. But that task is completely unnecessary because the power of Putain is the stark honest pain of being a woman in a man’s world.2 The pain of having to live up to male standards of how a woman is supposed to look. The pain of appealing to male fantasy (or rather delusion). The pain of being sagacious enough to realize the absurdity of exploiting the assets that come with transitory physical beauty which, especially as an escort, allows for a materialistic lifestyle with designer clothing and—inevitably—cosmetic surgery. It is an inescapable cycle of decline.

Unsurprisingly, Cynthia, the protagonist, reveals herself to have anorexic tendencies about halfway through the book. She is obsessed with her body image and is always working at making herself more attractive and sexier, but with the stipulation that increasing age on a woman is her eternal enemy, an enemy much more powerful than she. There will always be a younger more attractive woman or prostitute. Plastic surgery can only conceal so many wrinkles or markings of time. Arcan hanged herself successfully, after several failed suicide attempts, in her Montreal apartment at the age of 34 in 2009.

French Press Reporting on Arcan's Suicide

Although she had achieved literary stardom and had several novels to her credit, she was—at heart—the sad heroine of her first novel, obsessed with transitory physical beauty, the horror of traditional bourgeoise Québécois Catholic families and the implicit lies on which they are based, and—most of all—her disdain for herself as a woman, inferior to men, and the males who pay for her to play a role as they deceive themselves into thinking she might not be playing a role; that she might actually enjoy straddling an obese older man (and hearing about how the last prostitute he was with was too chubby and flabby) or that she might conceive pleasure in sucking old cocks that barely stay hard and listening to men make small talk, justifying their behavior.

Putain is a sad novel in the most beautiful sense of the word. Most works of arts about prostitution are from the male perspective. Thus, the depictions are often erotic and largely based on delusions.3 Hardly ever, in literature, do we encounter a female voice revealing how most women must really feel about this charade. Arcan is an anomaly in that she studied literature in a Canadian university and was able to accurately convey the contempt she feels for both for herself and her clients. She gives voice to women lured into the profession, not out of economic necessity or poverty, but due to an overwhelming sense of feeling inferior and trapped in a world built for men. She is a Little Red Reading Hood servicing the wolves. A putain who knows that her clients are fathers and husbands. And that all fathers are capable of being her clients, even her own.

Postscript: This was my third reading of Putain/Whore. My first was shortly after the English translation appeared in 2005, Whore. The second was in French a couple of years after Arcan’s suicide. Arcan’s French is meandering, gorgeous and non-linear, which makes sense because it is an extended monologue to her psychoanalyst à la Portnoy’s Complaint, but utterly bereft of the humor and titillating prose in the latter. I’ve previously written that Putain is a “kick in the nuts” to all heterosexual males, especially those who have paid for sex and that the book should be required reading; I thought about it often on ships near the end of my maritime career. Arcan’s perspective helped me behave in Saipan and Korea during deployments, though there is a different dynamic to prostitution in a seaport.

For this essay, I did a bilingual read, both editions, to be precise and to check up on my pitiful French. However, I ended up relying exclusively on the copy of Whore for the last 80 pages that I gave my partner, Alison, about 2017; I wanted to post an essay here in a timely manner. Alison scribbled all sorts of very apropos margin notes in pencil in the copy I gave her. Some of those thoughts inevitably appear in my essay.

I don’t want to overthink how Arcan differs from her heroine, Cynthia, as far as whether she was primarily an escort or whether she actually worked in a furnished room that could be reserved by men for an hour. Once her literary fame was established, she was marketed by her publisher, Éditions du Seuil, and the media as an “escort,” tacitly separating her from her own presumably honest self-assessment of herself as a “putain” or “whore,” the title she chose for her debut novel. In this essay, I have refrained from using those now derogatory descriptors unless specifically referring to the author’s word choice, which is meant to be derogatory. It is difficult to censor myself in that I’m such a Nelly Arcan fan that, after being obsessed with Arcan’s novel in both French and English for two decades, I feel that “whore” is the most accurate descriptor in English, even if it is currently verboten.

I remarked to Alison that for the cynically inclined, Nelly Arcan’s Whore and Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth are some of the strongest studies into how women feel about other women. Although the heroines stem from completely different milieus, the prose in both works drips with disdain. Unsubtle disdain in Whore, subtle in House of Mirth.

Just look at the above photo of the first French trade paperback. The book is anything but salacious, but you’d never guess that from the photo. At least the design of US edition makes an effort but also has a shadowy author photo alluding to captivating beauty. Really, whose author photo appears on the cover of a debut novel?